Modern Application Development Rhythm

Development Flow

Pivotal/Tanzu Labs

This article is the second in a five-part series.

A healthy, lean, modern application team has a strong and consistent Development Rhythm.

Developers who apply modern principles, practices, methods, and tools to software are able to add new features and fix existing issues faster, safer and more sustainably than ever before.

If you are a developer new to Agile concepts, and plan to work with Pivotal/Tanzu Labs on an upcoming engagement, continue reading this article, then go read the reference articles and do the workshops so that you are ready to be productive on your first day of work.

What you will learn

In this article, you will learn how to:

- Describe the Agile developer’s workflow.

- Describe the inputs to and outputs from the Agile developer flow.

- Explain the importance of developer discipline and the use of feedback loops in the developer flow.

Background

Before explaining the development workflow, it is useful to highlight principles found in modern Agile or Lean practices:

- Pull-based work model – downstream consumers pull work from upstream.

- Batch sizes are small.

- Use of short, feedback loops to iterate on the work.

- Integrate work with the team at least daily.

It is necessary to understand how the Agile developer’s flow fits into the overall software delivery cycle.

Let’s talk about upstream dependencies to the developer flow next.

Backlog

The Backlog is a curated list from which the developer will pull their work. Before a developer starts work, the work must be specified and prioritized in a backlog.

The work is specified as discrete User Stories that are:

- Specifications of what to build (or fix).

- Estimated by the team.

- Independent of each other.

- Prioritized.

- Sized small enough to be integrated daily.

Product teams typically organize work around features or fixes. Either may comprise work that is not small enough to fit in the confines of a single story.

Agile frameworks specify course grained work as an Epic or as a Theme, but neither the Epic or Theme directly specify the work done by the developer. Stories may be tied to Epics (or Themes) to keep the work to a specific feature or fix.

Outside the scope of the developer workflow, use of Epics and their relationships to stories are important when specifications are not well known, or when refining in-process work.

The input for an Agile developer workflow is a single story.

Software Delivery

The output of the Agile developer’s workflow is functioning software that is pulled into a downstream Continuous Delivery Pipeline for purposes of being able to deliver features or fixes to production at any time.

The Continuous Delivery Pipeline may involve various manual and/or automated steps for testing, verification, oversight compliance, staging, or perhaps a secure pipeline towards production.

Note: There is much more to this topic that is outside the scope of this article.

The Agile Developer Workflow

While the story provides a form of specification or requirement, it is up to the developer to translate the specification of the story into the design, tests, and their associated solutions.

The Agile development workflow compresses design, construction, and a substantial amount of testing into a story’s implementation work.

This places more burden on the developer and shows there is a need for discipline in the developer workflow.

Flow Summary

An Agile developer’s daily flow is similar to this:

- Take the highest priority story from the backlog.

- Review the story details, including its desired outcome. The story may be for building new features, fixing defects, or for an investigation if the problem/solution domain is not well known. If the story is investigative, the developer may use a Spike as a way to timebox effort to better understand a problem and/or its solution.

- Iterate on a series of steps using one or more feedback loops to achieve the outcome of the story. Developers spend much of their time writing code, using methods such as Test Driven Development, Refactoring and/or the Mikado Method.

- Document the work as appropriate and merge it to the source control repository once you complete all the steps.

- Verify the work is successfully integrated.

This entire flow should be run at least once per day, and ideally multiple times per day to satisfy the goals of Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery.

Developer Discipline

Although there are only five steps listed in the developer flow, there are many activities going on within it. It is important for the developer to keep focus during the workflow to work efficiently and effectively, yet also with the flexibility to change directions, as needed.

Even though the stories curated in the backlog are small, they do not specify the design. Agile approaches compress the design, construction and part of the test scope into the development flow by the same developer. This places a burden on the developer to be more focused and disciplined to craft quality software quickly and safely.

Discipline requires a set of clear, repeatable processes to be sustainable.

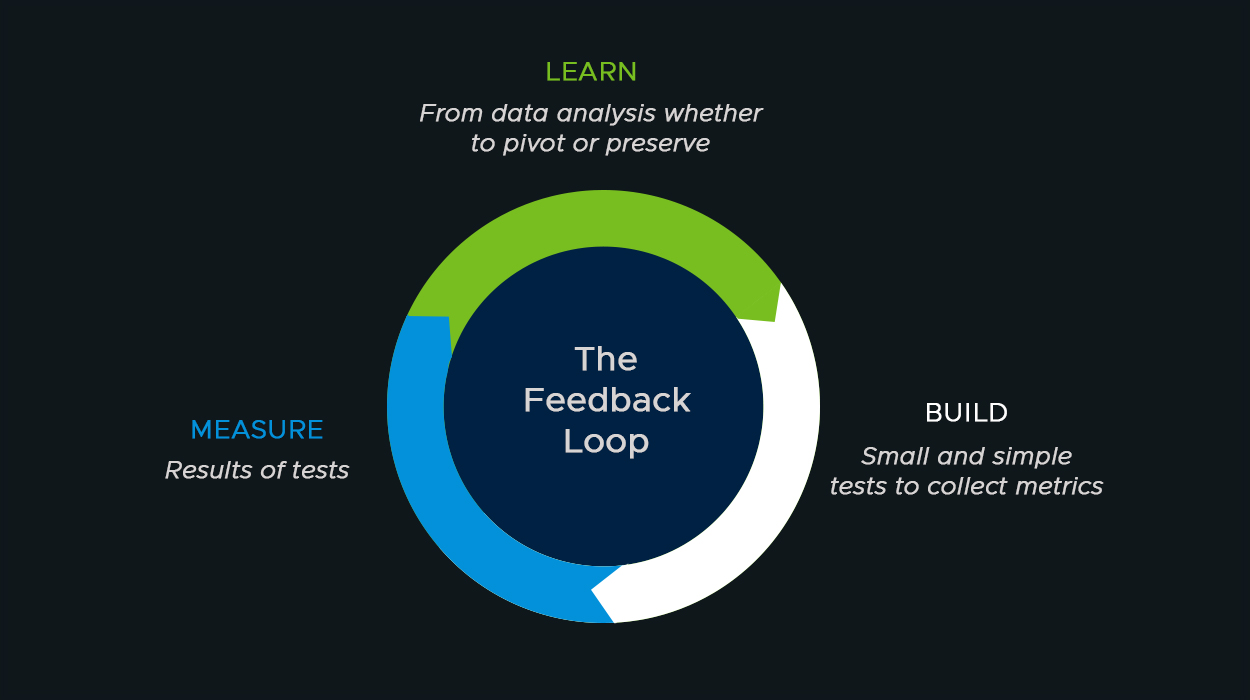

Feedback Loops

A common theme in modern application teams and their practices are use of feedback loops at varying levels in the application development lifecycle.

You can read more about it in the following articles:

The developers daily workflow also includes a series of fine-grained feedback loops. A single story might have hundreds of steps spanning multiple feedback loops to complete the story outcome.

While some of the steps are identified up-front when building and estimating the story, many of the steps are discovered during the workflow process in the form of multiple feedback loops that include a hypothesis and an associated experiment to verify that hypothesis.

It is necessary to keep each step in a feedback loop small in duration, measured in minutes, at a maximum, to run.

There are two reasons for this:

-

The overall work batch size remains small.

-

Humans work more efficiently doing small, well-defined tasks than large ambiguous ones.

The idea is to use evidence-based approaches to change, and that changes are easy to define, implement, and measure the outcome.

Development Inner Loop

As container and container orchestration technologies are becoming mainstream, development, testing and deployment become more complicated.

Another term you may see that relates to this subject is Development Inner Loop.

The idea is that the developer will iterate in their development environment (the Inner Loop), and then integrate their work in a DevOps Cycle (the Outer Loop) for continuous integration automated verification, and automation to support Continuous Delivery or Continuous Deployment.

Summary

In this article, you learned how to:

- Describe the Agile developer’s workflow.

- Describe the inputs to and outputs from the Agile developer flow.

- Explain the importance of developer discipline and use of feedback loops in the developer flow.

In upcoming articles, you will learn the key principles, practices, methods and tools to help implement your workflow.