Lean Experiments

A way to have your team create experiments to run so that you can validate or invalidate risky assumptions that may lead to product failure

Phases

Suggested Time

60-90 mins

Participants

Core team, stakeholders (optional)

Why do it?

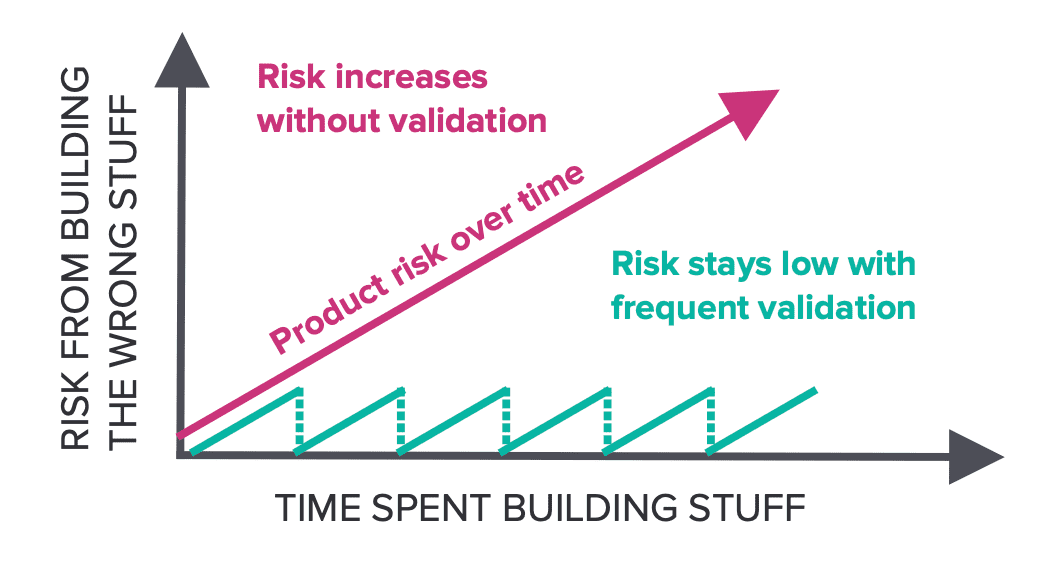

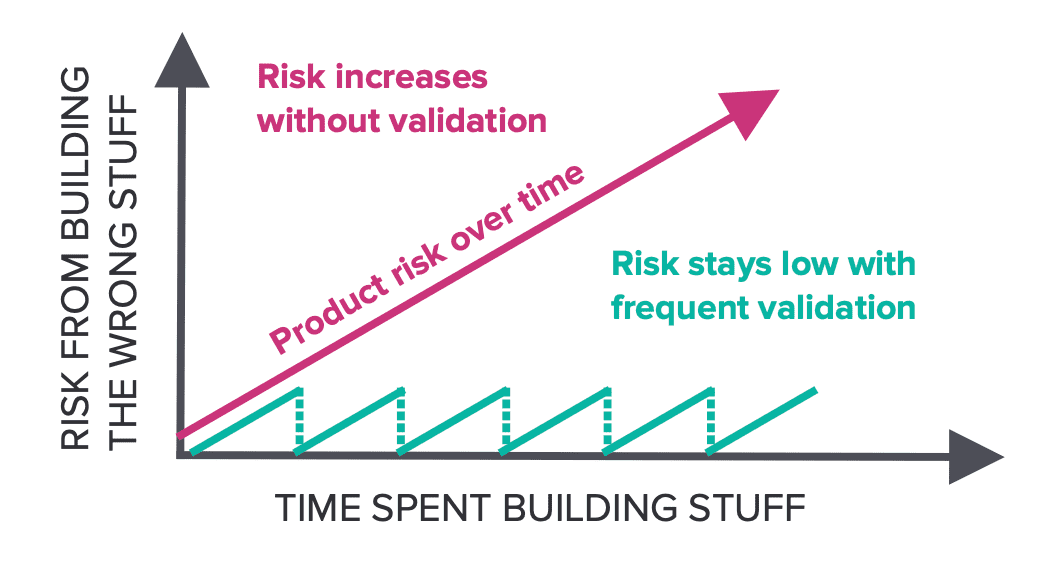

Lean experiments are useful when your team lacks evidence that a new product or feature will achieve its intended results. Running lean experiments alongside product development helps validate what is truly valuable to your customers/users, without incurring the cost of developing and maintaining production ready software.

When to do it?

During Framing of a D&F, at an Inception or throughout product development. Usually an Assumptions workshop has already been done.

What supplies are needed?

- Whiteboard or digital version like Miro

- Dry erase markers

- Markers

- Blank sheets of paper

- Sticky notes

- Sticky dots

- Painter’s tape

How to Use this Method

Sample Agenda & Prompts

-

Introduce the team to lean experimentation

Explain what Lean Experiments are, why we do them, and introduce common types of experiments.

“Lean Experiments are based on the Lean Startup approach to creating new products and services under conditions of extreme uncertainty. Lean Experiments are designed to quickly and cheaply gather evidence to validate or invalidate risky assumptions about your product.”

Common types of experiments:

A/B Test

A comparison of two versions of a product or feature to see which one performs best. Works best with large sets of users for small incremental optimizations of an experience and business model.

Concierge Test

A technique to replace a complex automated technical solution with humans who directly interact with the customer. Helps us validate whether anyone wants our product.

Wizard of Oz Test

A technique to replace the product backend with humans. The customer believes they are interacting with an automated solution. Helps us validate whether anyone wants our product.

Smoke Test

Commonly a website that describes the product’s value proposition and asks customers to sign up for the product before it’s available. Helps us validate whether anyone wants our product.

Tip: Feel free to come up with your introduction deck and examples. Prompt the room for a few additional examples to get them thinking in the right direction. Bonus points if you can find comparable examples to your own product space.

-

Catalog the team’s “leap-of-faith” assumptions

Add this term to the whiteboard, including the definition so that the team can refer to it throughout the exercise (Assumptions that if we’re wrong about, our product will likely fail).

Ask the team to brainstorm leap-of-faith assumptions on sticky notes for 2 minutes. If a team member comes up with more than two, ask them to self-edit down to those that are most important.

Catalog the product’s unvalidated, leap-of-faith assumptions on the whiteboard.

Tip: Try framing assumptions in the positive (users will feel safe getting into a stranger’s car) rather than the negative (no one will want to get in a stranger’s car). This will make it easier to reflect on how much evidence we have/need.

If you end up with more than a few leap-of-faith assumptions, prioritize one to focus on first. Use the Assumptions practice or consider a 2x2 with “more likely to stop the project” vs. “less likely to stop the project” on the Y-axis and “needs more evidence” vs. “have lots of evidence” on the X-axis. High likelihood of stopping the project assumptions that need more evidence are the target.

-

Explain that an assumption needs to be converted into a falsifiable hypothesis:

[Specific testable action] will drive [expected measurable outcome]

Introduce the format/template that you will use to track your hypotheses, experiments and measurements.

For example:

Describe what each of the following represent:

- Hypothesis — The thing we believe to be true

- Experiment — The test that we will run to validate our hypothesis

- Measurement — What signal we will look to for validation

- Outcome — The success and failure criteria

Tip: Don’t forget to timebox your experiments. The length of time you’ll have the experiment running should be defined up front.

Tip: If your team is not familiar with what makes good metrics, consider giving a primer or examples

-

Generate experiments

Distribute a sheet of paper to each team member and instruct them to:

- Copy the format of the Hypothesis & Experiment template

- Write the leap-of-faith assumption as a falsifiable hypothesis

Tip: If there are more than 4 participants, consider breaking into teams to generate experiments

Tip: Print out your templates, email/share them, or create and share the digital workspace before the workshop.

Feel free to copy this Miro board: Validation Research/MVP Experiment on Miro

Prompt everyone to take 5 minutes individually to think of an experiment to test the hypothesis and associated measurable outcomes. -

Share experiments

When time is up, have each team member (one by one) stick their sheet up on the wall and share the details of their experiment for group discussion.

Tip: Iteration on experiments from team feedback should be encouraged.

Give everyone 5 minutes to share their experiments.

-

Select an experiment

Explain that the best experiment should require the least amount of effort for the maximum amount of learning. Have the team members silently dot vote (1 or 2 votes depending on group size and # of experiments) on the experiment they think is best to run.

Tip: If you think the experiment could use refinement, consider prompting the team to redesign the experiment. Assign different team members to create experiments for the same hypothesis that take 2 days with $200, 2 weeks with $2000, and 2 months with $20,000. This should help find the right size for the experiment and encourage ways to learn smaller.

-

Discuss how to evaluate your experiments

With the experiment selected, talk through how to evaluate it. Typically experiments result in one of three learning outcomes, each with an expected next step:

- Uncertainty > test more & possibly iterate on experiment

- Validated > progress

- Invalidated > pivot

For any of the outcomes, record the results of the experiment and planned next steps. A good resource to leverage is The Learning Card from Strategyzer.

Tip: It’s good practice to set a super fail condition on your experiment. This is a failure so bad that it could indicate the experiment itself has an issue. We should believe something to be true in order to test it, so an epic failure should be unlikely.

-

Plan next steps & action items

Brainstorm and then assign actions for team members to take in order to execute the experiment.

-

Create an experiment tracker

Keep track of the experiments that were not selected in this session in a backlog. Regularly review these experiments and implement the experiments that are relevant to validate your product direction, especially if your product direction changes.

Success/Expected Outcomes

Success is when the whole team has aligned on a documented Lean Experiment that is ready to be executed on

Facilitator Notes & Tips

If there are many assumptions to validate, consider following up with a hypothesis/experiment tracker, as suggested in the last step above. This can help the team visualize what hypotheses should be tested in what order, and their associated experiments.

Related Practices

Preceding

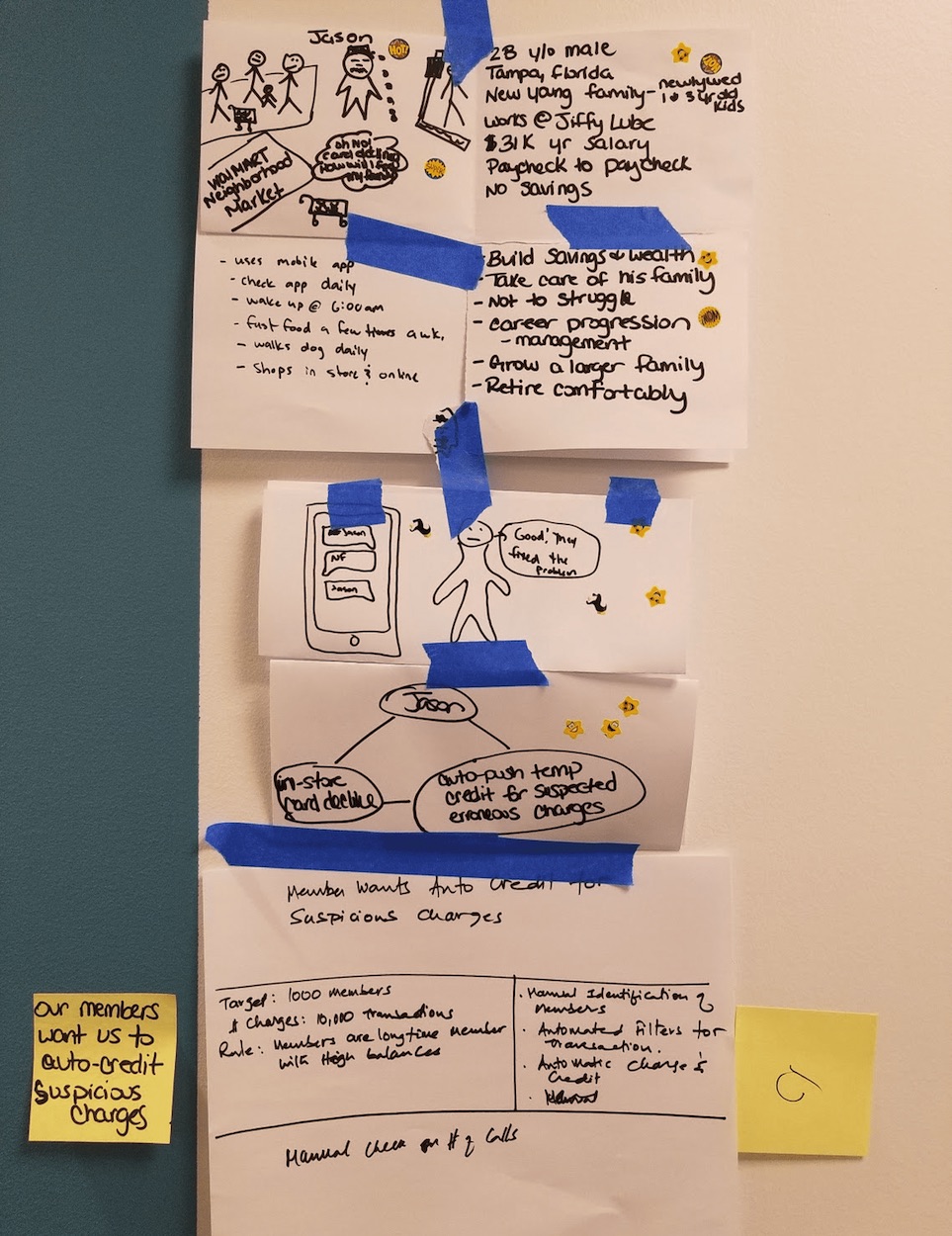

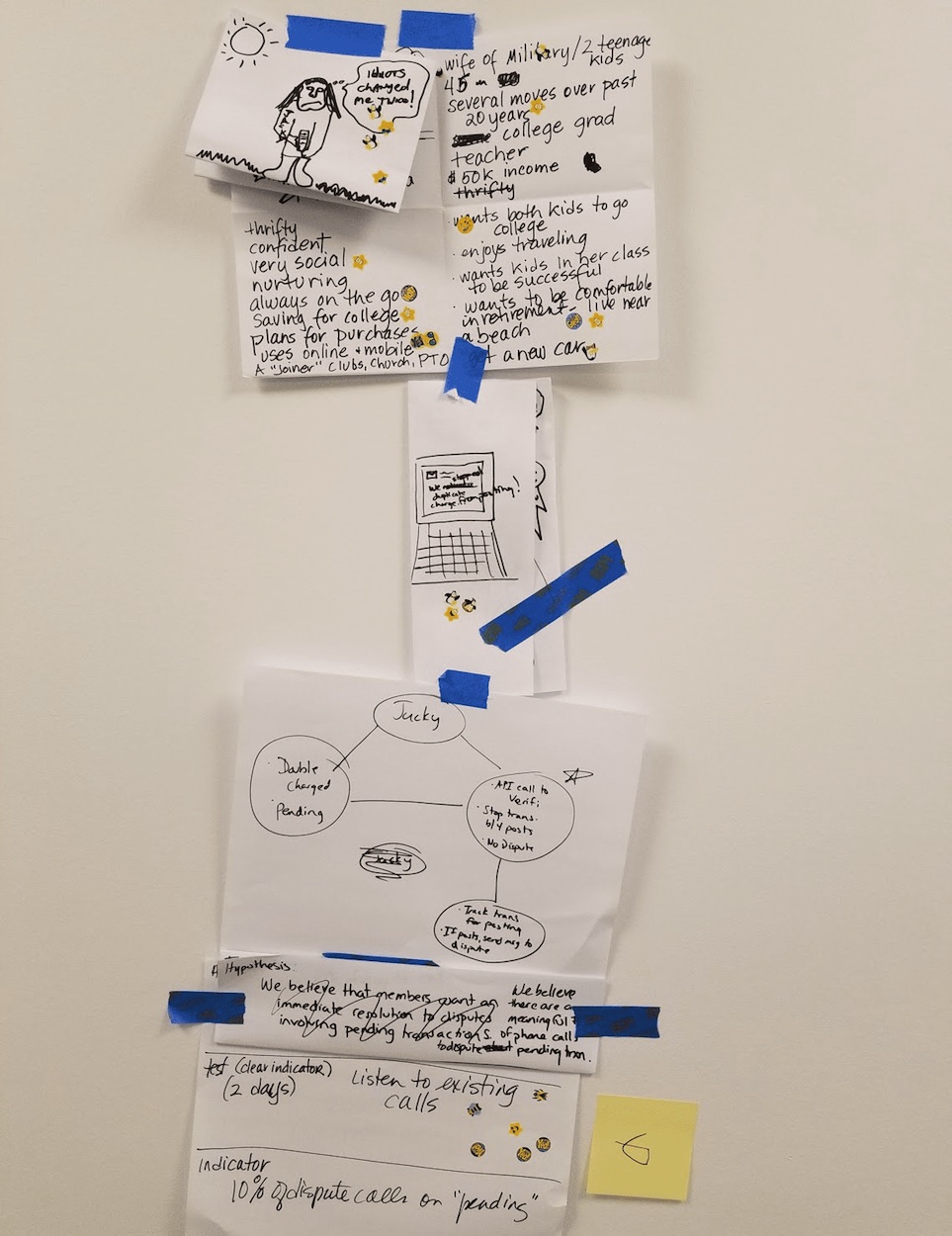

Real World Examples