Foundations of Modern Application Development Practices

Test Driven Development

Pivotal/Tanzu Labs

Test Driven Development (TDD) is a software development practice where a test case describing desired functionality is written before the production code. When that test is executed, it fails because the supporting functionality does not exist yet. After writing the minimum functionality to satisfy the test parameters, the code is refactored to improve the design. This cycle is repeated until all requested functionality is implemented. These tests serve as a guide for development of the production code by acting as the first “client” or “user” for the system. In addition, the tests provide a regression suite for the completed code.

What you will learn

In this article, you will learn to:

- Define End-to-End Tests

- Define Unit Tests

- Define Integration Tests

- Draw a “testing pyramid” representing End-to-End, Integration and Unit Tests

- Describe how TDD allows teams to go fast “forever”

Define End-to-End Tests

An End-to-End test exercises the system using the same interface that an end user would use.

For a web based application with an HTML user interface, these tests simulate user interactions via a web browser. They typically require a headless browser to be installed so that the computer running the tests can simulate browser based interactions. For an API-based application, these tests use API calls to simulate how a client application interacts with the system.

End-to-End Tests are relatively slow to run because simulating a user’s interactions, such as clicking buttons, uploading images, or API network calls can be slow operations. However, End-to-End Tests can give a team confidence that no user-facing interactions are broken when code changes are made. When writing End-to-End Tests, covering the major, important user flows allows a high measure of confidence while minimizing the time it takes to run a test suite.

Test-after vs. test-driven

When writing an End-to-End Test after feature(s) have been implemented, the team risks reinforcing incorrect behavior. For example, in a website you might build a test that replicates an existing navigation path even though that navigation path is incorrect.

When test driving, you might first write a navigation test that runs “click link A, then button B, then confirmation C” in correspondence with a new user story even though that navigation path does not yet exist. While implementing the functionality, run the tests regularly to verify the following one-by-one:

- First, the “click link A” test parameter fails because we haven’t implemented anything at all.

- After implementing link A, “click link A” passes, but “click button B” fails.

- After implementing that requirement, only “click confirmation C” is failing.

When everything passes, the user story is done.

Define Unit Tests

A Unit Test exercises a small part of the system that is isolated from the rest of the system. Sometimes it is a single class, file, or function, but it can also be a set of these that operate together through a single public interface.

Unit Tests are used as the primary design tool for inter-class interactions within a system. Because you are constantly running these tests to shape the system, you want to keep the feedback loops as quick as possible. By isolating these tests from the rest of the system and external dependencies like databases or network calls, they can run quickly for maximum speed of feedback.

Test-after vs. test-driven

As with End-to-End testing, writing tests after the production code is implemented risks reinforcing incorrect behavior. For example, you might observe that a function performing a complex calculation returns a value of “4200” and write that into your test validation, not realizing the correct calculation is “-4200”.

With test-driving, you set up the expected value in your test, asserting the calculated value is “-4200”. This test fails because you have not implemented the calculation yet; but, you’ve already worked out what the value should be in your test. Using this, you can implement the function and have confidence its correct when the test passes.

Define Integration Tests

An Integration Test exercises a subset of the system. They differ from End-to-End Tests in that they do not have to simulate user interactions and they differ from Unit Tests in that they exercise groups of “units” in one test.

Integration Tests operate on smaller parts of the system than End-to-End Tests, thus running faster. They also test larger parts than unit tests, thus running slower than unit tests.

Because they are “smaller” than End-to-End Tests, they can be useful in tracking down bugs because they encompass a smaller part of the system. However, because they are “bigger” than a Unit Test, they do not allow for the fine grained design feedback that you get with unit tests.

Draw a “testing pyramid”

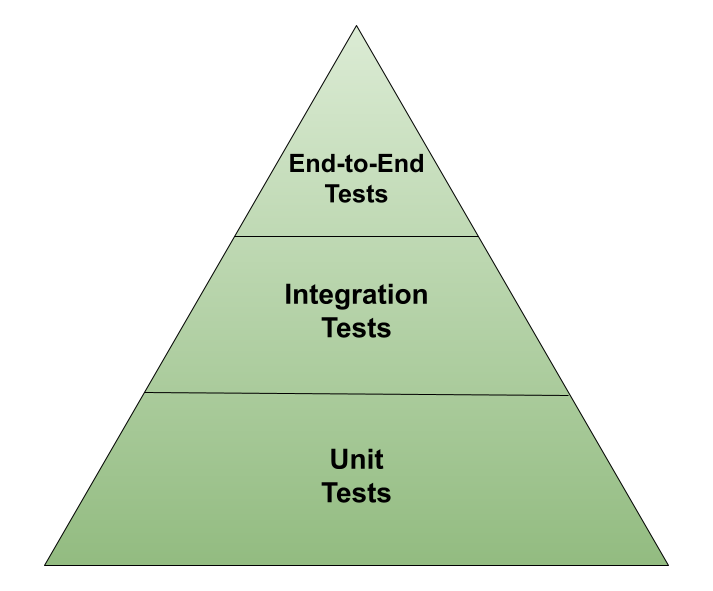

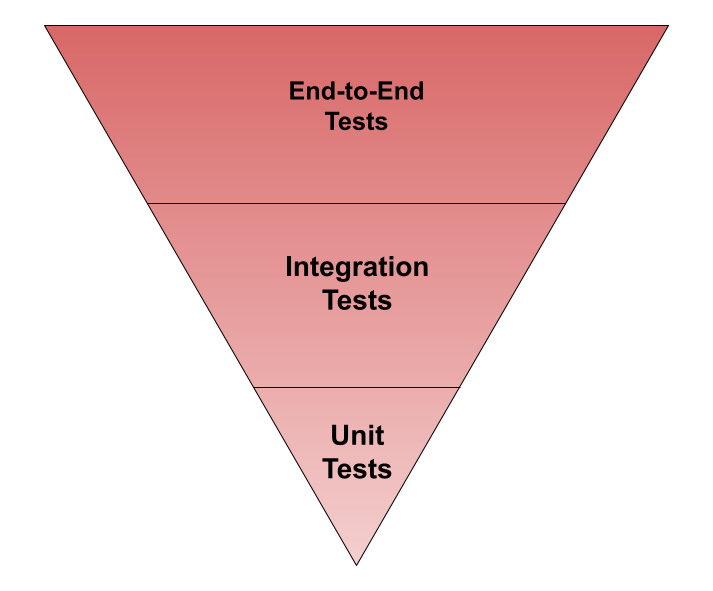

As you’ve learned above, tests can be written at different levels of the system. At each level, there is a balance between speed of execution, the cost to maintain the test, and the confidence it brings to the correctness of the system.

End-to-End Tests: Fewest and most expensive. End-to-End Tests are slower to run because they use simulated user interactions. They can also be fragile and susceptible to false-negatives because they rely on the quality and accuracy of user-simulation tools, such as web browser interaction tools, and other difficult to control factors, such as network latency.

In addition, changes to the user interface might require significant End-to-End Test rewrites even when the underlying functionality has not changed. These, and other related factors make End-to-End Tests “expensive” to maintain. You want to minimize the number of these to keep the test suite running quickly and minimize maintenance headaches while still covering the key flows of the system, either from a user interface or an API endpoint.

Unit Tests: Highest number and least expensive. You want the most Unit Tests in your test suite because they are the key way to design highly cohesive, loosely coupled software. Because you have kept them running quickly, the number of tests should not adversely affect the running time of the test suite. Also, the isolated nature of unit tests means changes in one area of the system do not require changes to other areas, making maintenance of Unit Tests minimal.

Integration Tests: somewhere in the middle. You want more Integration Tests than End-to-End Tests because they balance speed of execution and test maintenance with coverage of the system. However, too many Integration Tests can quickly slow down a test suite and make the feedback from the Unit Tests decrease in value.

A slow test suite is a signal that your testing pyramid might be “upside down” and you should focus more on Unit Tests to drive the design, and ensure the correctness of your software.

Describe how TDD allows teams to go fast “forever”

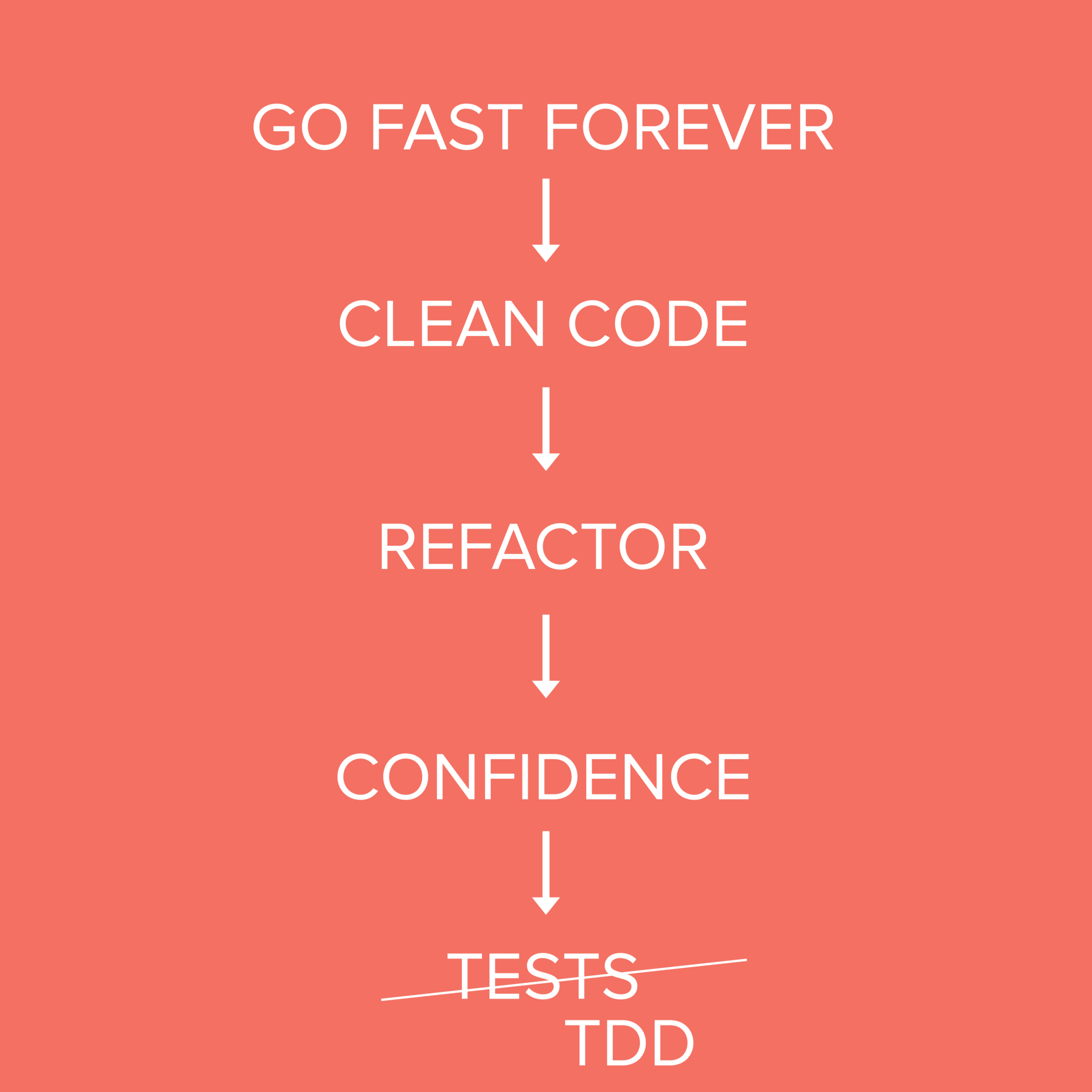

TDD gives teams the confidence to refactor application code to keep it clean so that they can go fast forever.

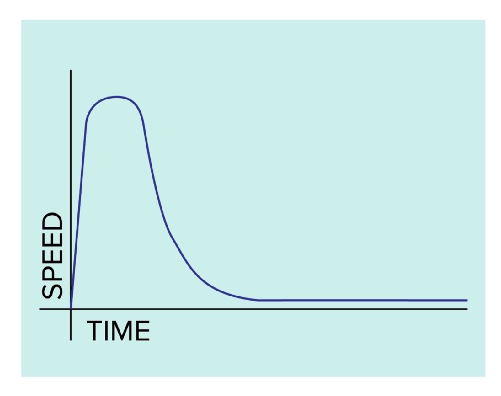

Going fast for a while

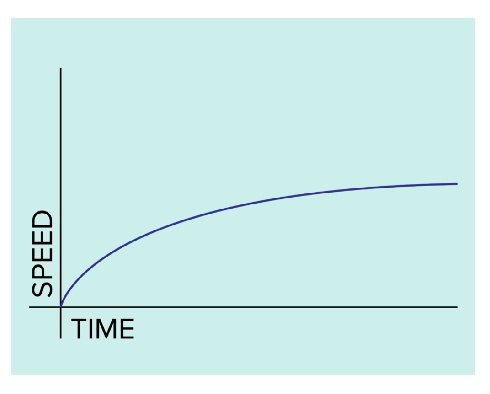

This diagram shows how a team just starting out can add functionality very quickly because they do not have a lot of code to work with. Unfortunately as time goes on and the codebase grows, the team can’t add functionality as quickly because the codebase starts to “resist” the addition of new functionality. This happens because the team has sacrificed long-term sustainability for short-term development speed. Eventually the rate of addition slows to a crawl.

Even small changes become increasingly complex due to highly coupled modules. Why?

- Developers fear changing the system because changes have unknown side effects.

- Knowledge of how and why the code works as it does decreases over time.

- Changes to the system result in regressions.

Going fast forever

In the second diagram, the codebase does not resist the addition of functionality as time goes on. Instead, it gets to a steady state of change velocity regardless of the length of time since the start of the project.

Changes are less complex, thanks in part to TDD helping enforce highly cohesive yet loosely coupled modules. Why?

- Developers do not fear changes because the tests clearly reveal any side effects.

- Knowledge of how and why the code works as it does is captured forever within the tests as “executable documentation”.

- Changes that would result in regressions are exposed in test failures.

There is a cost to these benefits. The initial sprint of functionality does not go as fast as forgoing TDD. This cost is the investment in writing tests before production code and only writing enough production code to make the test pass before writing another test. These tests serve as the guardrails that give the team the confidence to continually refactor their code to keep it clean.

In this article, you learned to:

- Define End to End tests

- Define Unit Tests

- Define Integration tests

- Draw the “testing pyramid” representing End to End, Integration and Unit tests

- Describe how TDD allows teams to go fast “forever”