Foundations of Modern Application Development Practices

Prioritizing Impactful Outcomes: User Stories, Estimation, and Velocity

Pivotal/Tanzu Labs

Being busy isn’t always the same as making progress towards an important goal. To make progress, the team has to know what to work on, why it is important, when one task is done and it’s time to move on to the next. The team also has to know what is the next most important and valuable thing to work on so they are always delivering the most impact to their end users. Using user stories estimated based on risk and complexity that are ruthlessly prioritized using that that information is the best way we’ve seen to consistently and predictably deliver value forever.

What You Will Learn

In this article, you will learn to:

- Define what a user story is and why they are useful.

- Describe the advantages of estimating work in terms of risk and complexity instead of time.

- Describe how measuring velocity enables teams to predict delivery.

Define What a User Story is and Why They are Useful

A user story is a short, simple description of a product feature told from the perspective of a user. It helps a team to understand what the feature is, who it is being built for and why it is valuable to build.

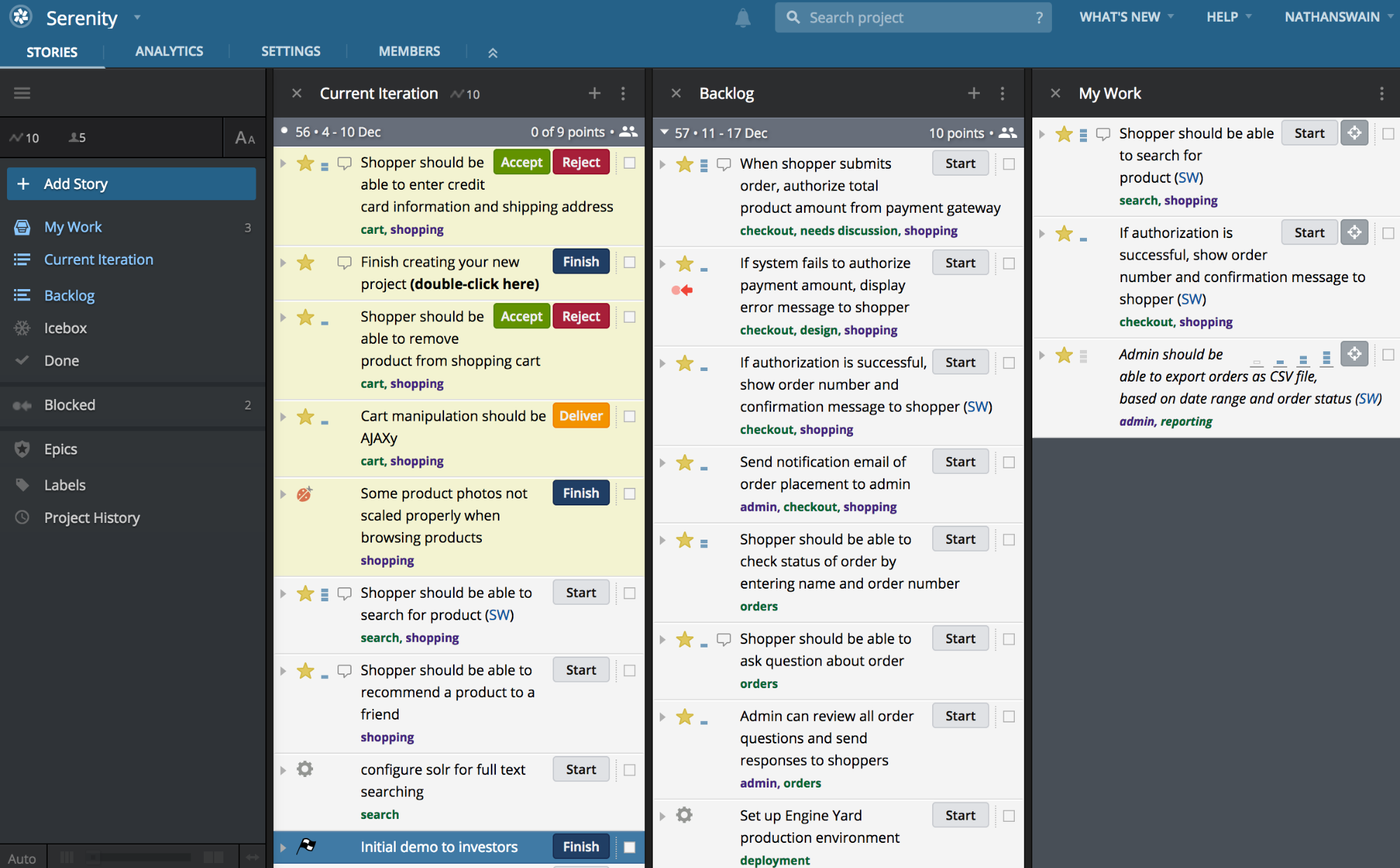

Anyone on a team can contribute stories, although it is typically the product manager’s responsibility to maintain and prioritize a healthy backlog of user stories. This includes writing and prioritizing enough user stories for a team to work on during a 1 or 2 week sprint or iteration of work. Learn more about the product manager’s role on the team in our Balanced Teams article.

Why User Stories are Useful

Stories are designed to help collaboration. Unlike weighty requirements documents, user stories capture just enough information for a team to start talking and working together. We sometimes say that a user story is a “placeholder for a conversation”.

User stories help break up software development into small, valuable increments. Building software incrementally, and prioritizing the work that delivers the most value reduces risk and helps a software team plan and get rapid feedback on what they are building.

A story’s position in the backlog makes its priority clear; the most important story is at the very top while the least important story is at the bottom. This makes it obvious which activity the team will work on next. A team’s backlog is prioritized based on input from users, stakeholders and the development team. When prioritizing, they’ll consider user value, business value, development risk and dependencies.

Finally, a user story provides a common way to talk about the goals, motivations, and definitions of success of your end users. By carefully crafting user stories based on an understanding of your users, you are more likely to build something that delivers value to them.

Structure of a User Story

Write user stories in a consistent manner that provides the team with enough context.

Common parts of a user story include:

Title

The title is a short description that explains the content of the story at a glance and is written from the perspective of a target user. The user might be a real human, a generalized persona, or even another software system.

Example:

A Sales rep can download a sales proposal as a PDF

Description

The main description of a story should explain which type of user wants the feature, what it allows that user to do, and what outcome or benefit this brings about. An established format is:

AS A type of user

I WANT some goal

SO THAT benefit for the end user

Example:

AS A sales rep

I WANT to download a PDF version of a sales proposal

SO THAT I can email it to a prospective customer

Acceptance Criteria

Acceptance criteria list the scenarios the product manager uses to verify that the story is complete. Behavioral Specification is a common format, also called the Gherkin language:

GIVEN situation or context

WHEN some action is carried out

THEN some consequences

Example:

GIVEN I visit the proposal summary page

WHEN I click the button labeled “PDF Download”

THEN a PDF file of the sales proposal downloads to my computer

Acceptance criteria is important because they clearly describe when the story is done. Without an explicit statement of “done”, the feature risks scope creep. In the above example, the feature is done when the sales proposal downloads to the user’s computer as a PDF file.

Would it be handy if the user could email the PDF directly from the product? Sure!

Would it be great if the system would automatically prompt the user to follow up with the prospective customer in one week? Heck, yeah!

But, those features are out of scope for this story. The team should create new stories for those features with their own explicit and focused acceptance criteria.

Resources

Attach anything else helpful explaining the story including mockups, sketches or user flows.

Here is a complete example:

STORY TITLE: A Sales rep can download a sales proposal as a PDF

Description:

AS A sales rep

I WANT to download a PDF version of a sales proposal

SO THAT I can email it to a prospective customer

Acceptance Criteria:

GIVEN I visit the proposal summary page

WHEN I click the button labeled “PDF Download”

THEN a PDF file of the sales proposal downloads to my computer

Resources:

- Example of this feature from one of our other products:

<link> - Developer note: here is the PDF conversion library our other teams use:

<link>

Describe The Advantages of Estimating Work in Terms of Risk and Complexity Instead of Time

Simply put: people are bad at estimating how long it will take to complete tasks. Yet most people insist on estimating task completion based on time. We recommend estimating tasks based on risk and complexity rather than time to completion.

Agile software teams use estimation to understand the relative complexity of delivering a story. They do this because:

- It helps the team understand and compare the development cost of new features, and make decisions accordingly.

- It allows the team to get to a shared understanding of the story and the risks or unknowns they could encounter.

- Over time, estimates can be used to predict how long it will take to deliver a particular feature or release.

When discussing a story, usually in an iteration or sprint planning meeting, teams will estimate the size of a story in terms of story points. Story points measure a story’s complexity and risk. Teams use different scales. For example:

- A simple scale of 1, 2, or 3 points

- “T-shirt sizing” as Small (S), Medium (M), Large (L), Extra Large (XL)

- The Fibonacci sequence: 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 (or more) points

We use scales rather than time estimates because time estimates are known to be highly error prone. They do not account well for the uncertainty that teams often encounter when building software. Time estimates are especially prone to planning fallacy and optimism bias.

Relative complexity means thinking about similar stories that the team has delivered in the past and making a relative estimate. This way, the team can build up a consistent, shared idea of what constitutes a small, medium or large-sized story.

When team members give different estimates for a story, this can give rise to valuable conversations! Estimation prompts team members to talk about their assumptions and arrive at a shared understanding of what is involved in the work. Learn more in our short guide to estimation.

Describe How Measuring Velocity Enables Teams to Predict Delivery

“When is it going to be done?”

– Your boss

Every team responsible for a deliverable has been asked this question.

Project teams commonly need to gauge how long it will take to deliver their work. Yet haven’t we just stated that we don’t recommend estimating work based on time to delivery?

Estimation gives the team data which helps them learn how to deliver more predictably over time and make predictions about future delivery.

To do this, we use the concept of velocity. You can calculate velocity by taking an average of the story points delivered in previous iterations. Once you know how many story points are left in your backlog, you can use your team’s velocity to forecast approximately how many iterations it is going to take to deliver the rest of the work.

Of course circumstances change and unexpected things happen, so predictions are never going to be 100 percent certain. To accommodate for risk, use a range of estimates based on optimistic and pessimistic scenarios.

If the number of story points a team delivers varies widely across multiple iterations, then the team’s velocity has high volatility. This makes it harder to predict delivery. It’s worth taking time with your team to understand why volatility is high and try to address it. Even uncertain estimates help to reduce and communicate risk, and make software delivery more predictable. Again, predictability and consistency are more important than raw numbers, and enable more accurate future planning.

In this Article, You Learned to

- Define what a user story is and why they are useful.

- Describe the advantages of estimating work in terms of risk and complexity instead of time.

- Describe how measuring velocity enables teams to predict delivery

Keep Learning

Find out how to run an iteration planning meeting, where your team will estimate and discuss user stories.

Read our blog post on how to write user stories that are easy to understand.

Learn more about user stories in User Story Mapping: Discover the Whole Story, Build the Right Product by Jeff Patton.

Related Topics

- Teaming

- Discovery and Framing process

- Agile

- Lean

- User Centered Design